Financial Sector Reform Program (FSRP) in Nepal and its Impact on the Performance of Nepal Bank Limited

Introduction:

Financial sector reforms are the activities or initiatives taken by the government and central bank to make financial sector more efficient, inclusive and risk resilient. It is continuous process implemented in order to improve the quality of financial services and the functioning of financial system as a whole. It may take several years to complete the proceedings.

During the late 20th and early 21st centuries, many countries particularly in Asia and other emerging markets undertook major financial sector reforms to address banking crises, strengthen regulatory frameworks, and align with international standards such as those set by the Basel Committee for Banking Supervision (BCBS). Global financial institutions like the World Bank and IMF actively promoted reforms that emphasized prudential regulation, corporate governance, and modernization of banking operations. Nepal’s financial sector, which had long been characterized by state dominance, weak supervision, and high levels of non-performing assets, could not remain isolated from these global developments. In this context, Nepal launched its own Financial Sector Reform Program (FSRP) in the early 2000s, targeting systemic weaknesses and aiming to restore stability, efficiency, and competitiveness. As the country’s first commercial bank and one of the most distressed institutions at the time, Nepal Bank Limited (NBL) became the focal point of these reforms. Examining the impact of these reform measures on NBL offers valuable insights into how global reform trends were localized to meet Nepal’s specific challenges. This article reviews how those reform programs led primarily by Nepal Rastra Bank (NRB) with support from the World Bank, IMF, ADB, and bilateral partners shaped the route for enhancing NBL’s performance. It synthesizes evidence from policy documents and supervisory reports to trace changes in asset quality, profitability, governance, and technology, and to note remaining challenges.

Need of reform in financial Sector of Nepal:

Nepal’s financial sector reform program was initiated in mid 1980’s and it is still being pursued. By the early 2000s, Nepal’s banking system suffered from political interference, weak supervision, and very high non-performing loans (NPLs). NBL and Rastriya Banijya Bank (RBB) in particular faced severe solvency and liquidity stress. In response, the government adopted a comprehensive Financial Sector Reform Program (FSRP) in 2001–2002, alongside a new NRB Act (2002) to strengthen central bank autonomy and supervisory powers. NRB is implementing financial reform program via monetary policy every year.

Objectives of FSRP in Nepal:

The financial sector reform program in nepal aimed to improve overall performance and governance of nepalese financial institutions. The specific objectives of program were:

- To cope up with the threats of global competitiveness in carrying out the financial services.

- To increase the qualitative and quantitative performance levels of BFIs.

- To establish and improve internal management system, risk analysis practices and governance levels within the BFIs.

- To reform and address the legal shortfall associated with regulation

- To provide a wider range of financial services at lower costs while minimizing financial risks to a large number of customers.

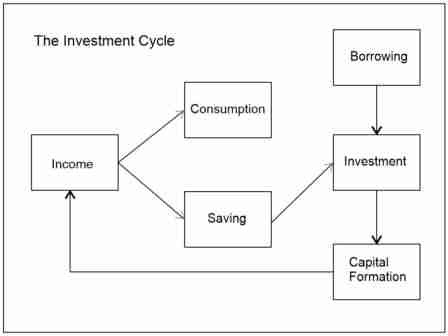

- To induce investment, increase employment opportunities and productivity, achieve growth targets and attain overall macro-economic development.

Reform instruments applied to NBL and their impact:

Financial sector reform was mostly intended to improve the strength and performance of government sector banks specially NBL and RBB. From standpoint of NBL, it started with the appointment of an ICC Consulting management team at NBL on 21 July 2002. Afterwards, the reform measures at NBL included;

- Appointment of an external professional management team to stabilize operations and prepare the bank for resolution/privatization options: The appointment of an external management team (ICC Consulting, July 2002) helped break the cycle of political interference and mismanagement that had plagued NBL. This professional oversight restored operational discipline, implemented modern management practices, and set the foundation for restructuring. It also boosted stakeholder confidence including depositors, regulators, and development partners that the bank could stabilize and return to viability.

- Aggressive NPL resolution and provisioning: Before reforms, NBL’s non-performing loan (NPL) ratio was among the highest in South Asia (around 58% in 2003). Through stricter loan classification, recovery drives, write-offs, and provisioning, the bank drastically reduced its NPL ratio to below 6% within a decade. This strengthened its balance sheet, restored financial soundness, and signaled improved credit discipline in Nepal’s banking sector. It also created room for the bank to expand new lending on a healthier foundation.

- Recapitalization and balance-sheet cleanup measures: Recapitalization and cleanup allowed NBL to absorb legacy losses and meet regulatory capital adequacy requirements. Rights share issues, conversion of government borrowings, and provisioning adjustments strengthened its capital base. These steps ensured compliance with prudential norms, safeguarded depositors, and provided a platform for sustainable growth.

- Modernization of systems and processes: The reforms introduced a technology transformation, including the adoption of a core banking system (CBS), computerized accounting, and better management information systems (MIS). These changes improved transparency, risk management, and efficiency. Customers benefited through modernized banking services like electronic transactions, faster processing, and enhanced accessibility, which aligned NBL with emerging competitive standards in Nepal’s banking industry.

- Strengthened governance under strong NRB supervision: NRB’s enhanced supervisory authority after the 2002 NRB Act meant NBL was subject to stricter prudential regulation and monitoring. This reduced political capture, enforced accountability, and required the bank to adhere to international norms such as Basel-based loan classification and provisioning standards. Stronger governance improved investor confidence, reinforced internal risk management, and promoted long-term institutional stability.

Improvements visualized in NBL’s Performance:

Aforestated reform programs applied in NBL created multi-dimensional effect in the strength and performance. It boosted the confidence of all stakeholders of the bank to make it more stronger and risk resillient. The main visible improvements are highlighted as following:

1) Asset quality and solvency effects

The most visible improvement was in asset quality. According to World Bank restructuring documents, NBL’s NPL ratio fell from roughly 58% (mid-July 2003) to about 5.3% seven years later, reflecting intensive loan classification, recovery, and write-off efforts alongside tighter supervision. This change materially reduced expected losses and capital strain.

2) Operational and financial performance

World Bank progress reports during the restructuring period note that, after external managers took control, both NBL reduced operating losses and improved cash flows, reversing years of deterioration. However, at a whole-project level the Financial Sector Restructuring Project later received a mixed evaluation illustrating that while bank-level turnarounds were achieved, broader systemic outcomes were uneven. For NBL, the operating turnaround, falling NPLs, and better provisioning translated into improved profitability and resilience relative to the pre-reform baseline.

3) Governance and supervisory discipline

The reforms strengthened NRB’s authority and introduced a more rules-based supervisory approach (e.g., loan classification and provisioning standards, enforcement actions). For NBL, this meant closer oversight, time-bound corrective programs, and performance benchmarks under the restructuring framework mechanisms that curbed political interference and forced operational discipline compared with the 1990s.

4) Technology and service modernization

Reforms were not only about balance sheets. NBL’s “technology transformation” began under the World Bank/DFID-supported program, with the external management team catalyzing core-banking implementation (e.g., CBS “NEWTON” and “PUMORI”), electronic operations, and process automation. These steps supported scale, internal controls, MIS/reporting, and customer service modernization through the 2000s and 2010s.

5) Recapitalization and liability management

As legacy losses were recognized, NBL undertook capital measures (e.g., rights share adjustments and government-linked conversions of obligations), consistent with a multi-year cleanup. Public documents from the bank note government decisions around treatment of borrowings and share adjustments during the post-reform period, aligning the capital base with prudential norms.

Major Challenges in FSRP success:

Financial Sector Reform Program Implemented in Nepal through four phases got considerable improvement in the financial performance of specially state owned commercial banks like Nepal Bank Limited. But, due to some hurdles and challenges program was unable to produce expected results. Major challenges of program are:

- Lack of Government commitment to change its basic mindset towards state owned BFIs.

- Absence of action program to introduce drastic changes in the managerial culture to ensure that managers were professionals with autonomy and accountability.

- Financial accounting is in implementation phase and not fully according to international standards.

- MIS and record keeping are very in basic stage.

- Governance and management are highly politically driven and lacking a commercial focus.

Lessons learnt from FSRP:

FSRP implemented from 1980s made tangible achievements in developing legal and regulatory frameworks along with flourishing FIs in Nepal. The reform also highlighted the role of private sector by reducing the dominance of state-owned banks. But the program failed to alter the fundamental weakness of the Systematically Important State-owned banks such as weak governance and management, inadequate risk management, Deficient staff skills and redundancy and highly politicalized labor unions. Financial distress happens in state-owned banks when the government intervenes for political motives. So, it is better to privatize the state-owned banks. Internal development agencies are the driver of finance sector reform program and their continuous engagement is inevitable. Capacity of NRB is key to the success of FSRP. Structuring via external management is not sufficient and effective without proper coordination between government and donors.

Conclusion:

Financial reform programs since 2001 fundamentally changed Nepal Bank Limited’s trajectory. The combination of external professional management, enforced prudential standards, and technology upgrades reduced NPLs, restored operating performance, and improved governance compared to the pre-reform era. While system-wide reforms received mixed scores at the project level, NBL’s bank-specific outcomes especially the dramatic fall in problem assets and modernization of operations stand out as concrete successes. The enduring lesson is that autonomy for supervisors, credible management, transparent loss recognition, and investment in systems are mutually reinforcing. Despite significant progress, sector-wide analyses caution that headline NPL and capital figures in Nepal can be flattered by practices like evergreening and under-provisioning, implying ongoing supervisory vigilance is essential. For NBL, sustained attention to risk management, governance quality, and independent credit processes remains critical to lock in reform gains particularly through economic cycles. To preserve these gains, NBL must continue to strengthen credit underwriting, provisioning discipline, and governance, while NRB maintains firm, risk-based oversight.

References:

Nepal Rastra Bank. “Financial Sector Reforms in Nepal.” (NRB Economic Review article; background on FSRP origins and priorities).

World Bank. Financial Sector Restructuring Project—Project Information/Progress Documents. Evidence on turnaround in NBL/RBB operating performance and project ratings.

Nepal Rastra Bank. Annual Bank Supervision Report 2002/03. Records appointment of ICC Consulting external management team for NBL (21 July 2002).

World Bank. Restructuring Paper/ICR materials on Nepal Financial Sector operations. NBL NPL decline from ~58% (2003) to ~5.3% (around 2010).

Nepal Bank Limited. “NBL Technology Transformation.” Notes CBS adoption and modernization steps under the reform program.

Nepal Bank Limited. AGM/Audited Financial Results (FY 2071/2014). Illustrative disclosures on capital actions during the post-reform clean-up.

IMF. Nepal—Selected Issues (2008). Background on restructuring support for NBL and RBB and state ownership context.

World Bank. Nepal Development Policy Credit (2013) press release. Context on continued financial-sector reform support.

World Bank. Financial Sector Assessment/Notes (2017). Caveats on system-wide NPL and capital quality (evergreening/under-provisioning risks).